The destruction of Hungarian Jewry

Click here to learn about this photo:

Interviewed by Mihály Andor for Centropa in 2007

Vera Szekeres Varsa shared with us her life story, which is not yet available on our website in English. Vera is pictured in this photo in 1944 with her parents, Dr. Józsefné Varsa (Ilona Garai-maiden name) and Dr. József Varsa. The family lived in Budapest and survived the war in an apartment on Király street in Budapest with Lutheran papers. Vera went on to become a language teacher in elementary schools and had one daughter in 1953 exactly on Vera’s 20th birthday.

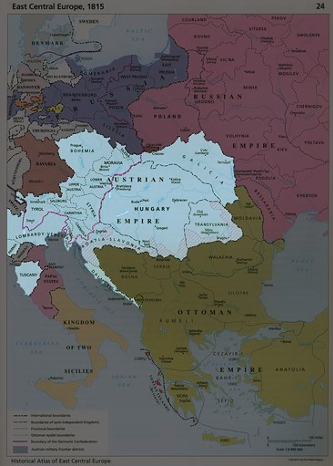

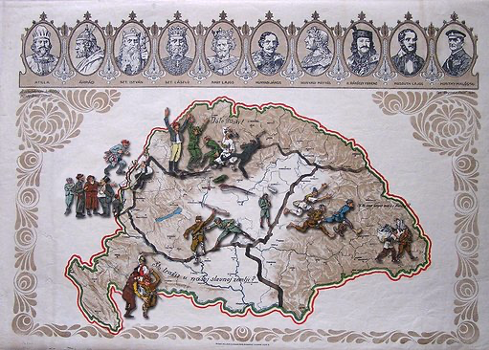

When the twentieth century began, 911,000 Jews lived in the Hungarian lands of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. They ranged from Yiddish speaking, orthodox Jews in small towns and shtetls, to secular, assimilated Jews in Budapest, Szeged, Kassa and Kolozsvar. 203,000 Jews lived in Budapest, making up a fifth of the population.

While the majority of Hungary’s Jews were working class and struggled to make ends meet, 60% of the country’s merchants were Jewish, 48.7% doctors were Jewish, as were around half of her lawyers (doctors and lawyers earned considerably less at that time than many do today). Jews could also be found in the upper reaches of finance and industry and 350 Jewish families had been ennobled with the titles of barons and counts.

Hungary’s Jews won Olympic gold medals and were awarded Nobel Prizes. And when the First World War began in 1914, tens of thousands of Hungarian Jewish men volunteered or were called up for military service. 10,000 fell fighting for the Empire.

After the First World War, the victorious Allies stripped Hungary of two thirds of its territory and a rightist government under Admiral Miklos Horthy took control and passed the first laws restricting Jewish enrollment in universities with the 1920 numerus clausus law.

Hungary slowly began to stabilize itself economically until the Great Depression of 1929. Once Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party took control of Germany in 1933, he pulled Hungary into Germany’s economic orbit, step by step, while the Hungarians remained focused and obsessed with retrieving their lost territories.

In 1940, Hitler took northern Transylvania from Romania, Vojvodina from Yugoslavia, and bits of Czechoslovakia and handed them back to Hungary. In return, when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June, 1941, Horthy sent his army to fight alongside the Germans. It would prove to be a slaughter as the Hungarian Army was poorly equipped and demoralized even from the beginning of the invasion.

Tens of thousands of unarmed Jewish men went with the Hungarian army and served in forced labor brigades, and around 25,000 perished while serving.

Yet Hungary was an ally of Nazi Germany, not occupied by it. By the end of 1943, the overwhelming majority of Jews in Poland, the three Baltic states, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Greece and much of what is now modern day Ukraine had all been murdered. Yet every day, Hungarian Jews were going to work, studying in school and attending synagogue services.

The photograph taken above in the Dohany Synagogue in Budapest in 1942 (Click here) tells us much. These are retired Jewish army officers attending a prayer service, and they have been given pride of place in the synagogue’s front rows.

With the Allies already fighting their way up the Italian peninsula and Stalin’s Red Army marching toward the west, Admiral Horthy sent out feelers to the Allies to take Hungary out of the war. Once Hitler learned of this, he launched Operation Margaethe, and on 19 March 1944 German Wehrmacht troops marched into Hungary unopposed.

Far worse was that Adolf Eichmann arrived with a contingent of less than two hundred SS men, and in very short order, Hungary (and in the occupied territories named above) was divided into twelve zones of occupation. With the full cooperation of the Hungarian police and the municipal authorities, hundreds of thousands of Jewish citizens were herded into ghettos starting on 16 April—almost always near brick factories next to the local train yards—beaten into revealing where their “treasures” were hidden and packed into freight trains.

A total of 437,402 Jews were deported in less than fifty-six days and almost all of those were sent directly to the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau. A few thousand returned alive.

Budapest was saved for last, but by the time Eichmann began his deportations, Admiral Horthy, succumbing to pressure from President Roosevelt, the Papal Nuncio and others, halted all deportations on 9 July, 1944. A few weeks later, Raoul Wallenberg, a wealthy Swedish diplomat, arrived in Budapest and began handing out protective papers, as did Carl Lutz from the Swiss Embassy and Angel Sanz Briz, the Spanish ambassador.

On 23 August, four days after the Allies liberated Paris, King Mihai of Romania deposed strongman Marshall Ion Antonescu, and immediately switched sides by welcoming the Soviet Army, which sped through Romania and headed into neighboring Hungary.

On 15 October, Admiral Horthy tried to do the same, but Hitler had him deposed and flown to Germany while the murderous Hungarian Nyilas, or Arrow Cross, took control under Ferenc Szalasi. Arrow Cross soldiers began to run amok, slaughtering Jews on the streets, in their homes, and marching hundreds to the banks of Danube and shooting them on its banks.

Jews were forced into yellow star houses, tens of thousands sent in labor brigades toward the Austrian border, and on 29 October, more than 70,000 Jews are huddled into the newly created Budapest ghetto while the Soviets begin shelling the city and advancing into it. The ghetto had almost no running water, little electricity and no heat. More than a dozen people were herded into each room of the ghetto.

On 18 January the Soviet Army broke through and liberated the Budapest ghetto, then laid siege to the last German stronghold on Castle Hill, taking the rest of the city by 13 February. The Soviets would then chase the Germans all the way to Vienna, which it took on 15 April, 1945.

Hungary’s Jews began returning home from forced labor and concentration camps and with the communities in the countryside all but devastated, Hungary’s Jews—traumatized, horrified and in mourning—started to rebuild their lives. Almost all of them settled in Budapest.

Over the coming years, around tens of thousands of Jews would leave Hungary, but tens of thousands chose to remain. Many of those who remained wanted nothing more to do with Judaism. Many of those who left wanted nothing more to do with Hungary.

After four dark decades of Communist rule, Hungary became a democracy once again in 1989, and today, more Jews live in Budapest than in the rest of Central Europe—combined. Despite the trauma of the past, Budapest’s Jewish community is the liveliest in the region, with four Jewish schools, youth clubs and Jewish community centers, and dozens of bar and bat mitzvahs taking place every year.