Jozsefne Erzsebet Barsony

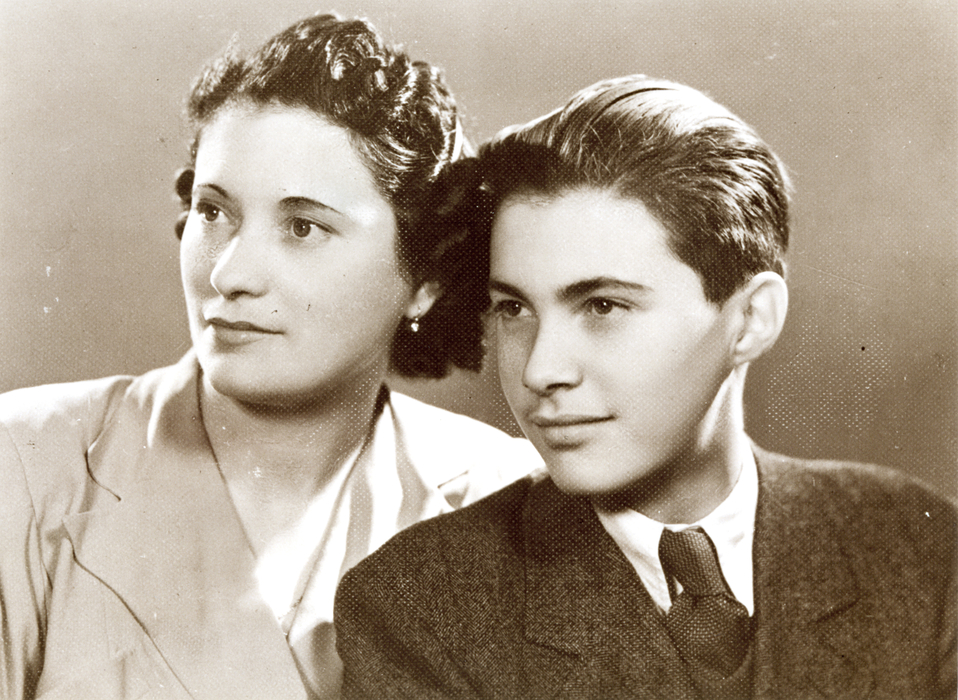

Jozsefne Erzsebet Barsony and her son Ervin Fenyes

Ervin Fenyes as an actor of a school play

Interviewee: Jozsefne Erzsebet Barsony

Interviewed by Klara Lazok and Viktoria Kutasi in Budapest, 2004-2005

My son, Ervin Fenyes, and me, taken in Budapest around 1943. Ervin was born on 25 July 1929.

In July 1944, they deported my son and me in cattle cars, and there was an incredible crowd. We traveled for three days, day and night, in awful conditions. We could hardly sit. My child was about 192 centimeters tall (6 foot 3 inches), and the poor thing had to be folded as a folding ruler. He always wanted to look out the lattice window.

After three days, on 12 July, we arrived in Birkenau. We were set down; everyone took his belongings and tried to protect themselves against the heat. The first thing they did was separate me from my child, telling everyone in which group to stand. There was such confusion in my head I couldn’t even comprehend it. I was standing there with my emotions numbed. Then my son turned up, hugged and kissed me, and told me in tears, ‘Mom, you’ll see, we’ll meet again!’

I just kept telling him, ‘Go back, my son, go back. So that nothing will happen.’ And poor him, he tried to comfort me. It was a horror. I never saw my 15-year-old son again. My son, who had been playing the violin for nine years, and was going to the conservatory, and whose teachers had great hopes for him! He wanted to be an artist, a violinist. Nothing has become of him.

Read the interview with Mrs Barsony here

Read the original Hungarian language interview here

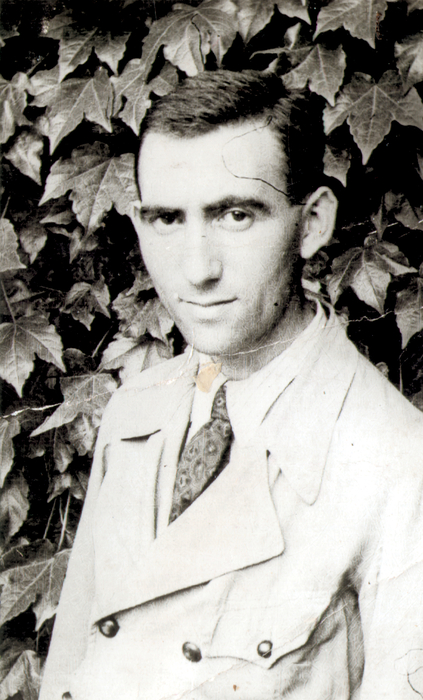

Ferenc Deutsch

Iren Klein in her wedding dress

Ferenc Deutsch in his garden

Interviewed by Dora Sardi and Eszter Andor in Budapest, 2001

My first wife, Iren Klein. Our wedding was in 1941 in Ujpest, in the synagogue on Beniczky street.

I was considered an indispensable war-factory worker while working at the Wolfner factory, which is why I was not deported. I cooked for about 300 people. We celebrated Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah in the bunker under police surveillance. The policeman in charge ordered the Torah to be brought so we could celebrate our festivals.

My pregnant wife was being deported in July 1944. When I found out, I wanted to go with the family, so I jumped over the fence. I was caught and tried by military tribunal. One member of the tribunal was very kind; when I told him that Iren was pregnant and I wanted to join her, he was lenient; he could have had me shot but he let me go. Iren was taken to Auschwitz with my mother-in-law and both were sent to the gas chamber. My father-in-law told me this when we met in 1945.

Read the english interview with Ferenc Deutsch here

Read the hungarian interview with Ferenc Deutsch here

Gyorgyike Hasko

Gyorgyike Hasko with her parents and her brother

Interviewed by Judit Rez in Budapest, 2005

On the 19th of March, the Germans marched in. I was on duty in class that week, when the children left the room during the recess, I opened the window overlooking the Danube, and I don’t know how I knew, but I knew that the Germans were marching in and I knew exactly that I had to hate them. I was watching how the Germans marched on the lower embankment, and I knew precisely that there was trouble.

The news that the Germans came in started to spread among the teachers in seconds, and they quickly sent us home. When they marched in, a massive army made its entry into the city and scouting airplanes flew up in the air to frighten us or protect the army. Those planes were black as far as I remember and flew close to the ground. It was so horrible that by the time I got home I was shaking!

All along the Basilica to Paulay Ede Street on foot, I can’t even describe that fear! My father was deaf, he sat at his desk, and the phone was next to him, but he didn’t hear the doorbell. I went home and stood at the entrance in the outside corridor, these airplanes above me, and I rang in vain.

The events happened as fast as lightning: they disconnected the phones in Jewish apartments, we had to surrender our radios, and soon we had to go to a yellow star house.

Paulay 12 didn’t become a yellow star house, so we had to move.

The family was saved with Swedish Shutzpasses and Raoul Wallenberg’s help. They received medical help and accommodation in Swedish Safe Houses.

Györgyike married in July 1951, and had two children, a boy and a girl. Nowadays she works at the Federation of Hungarian Communities.

Read the english interview with Gyorgyike Hasko here

Read the hungarian interview with Gyorgyike Hasko here

Gáborné Révész

Interviewed by Szilvia Czingel in Budapest, 2006

It was Sunday when the German occupation began. I was just heading home from school across Margaret Bridge.

My mother and I were sitting at the table for our Sunday midday meal when the bell rang. I saw a policeman standing there. I got terribly frightened, but he said to let him in because he’d brought a letter from my sister, Magdolna. She had been taken to the internment camp at Kistarcsa and wrote this letter on a tiny piece of paper in minuscule handwriting. She used such a small piece of paper so the policeman shouldn’t get into trouble.

We later learned that she had been deported to Auschwitz and we got a postcard from her, written in German. It contained a prescribed text in her own handwriting, in German. It said that she’s fine and everything is OK. The stamp said Waldsee, which was the cover-name for Auschwitz.

The news that the Germans came in started to spread among the teachers in seconds, and they quickly sent us home. When they marched in, a massive army made its entry into the city and scouting airplanes flew up in the air to frighten us or protect the army. Those planes were black as far as I remember and flew close to the ground. It was so horrible that by the time I got home I was shaking!

All along the Basilica to Paulay Ede Street on foot, I can’t even describe that fear! My father was deaf, he sat at his desk, and the phone was next to him, but he didn’t hear the doorbell. I went home and stood at the entrance in the outside corridor, these airplanes above me, and I rang in vain.

In 1944, they made people who were taken there to write these letters to calm everyone down at home. Later, when they deported Jews from the countryside by the tens of thousands, they didn’t bother because there was no one to write to, anyway. They were all taken away.

After the war, my mother received a letter from a woman doctor who described what happened to my sister. They were on a forced march from Auschwitz towards Hannover. My sister was not in a bad physical state, but her spirit was broken, and she gave up the struggle. This is how we found out that she died in May 1945.

Read the english interview with Gáborné Révész here

Read the hungarian interview with Gáborné Révész here

Heni Szepesi

Interviewed by Dora Sardi and Eszter Andor in Budapest, 2001

The Germans came in on the 19th of March, 1944; on April 5th we all had to wear a yellow star. Then we heard that those who would go to Sopronpuszta to work as farm laborers, young people, would not be deported.

We were put on the trains on the 5th of June and on the 8th we arrived at Auschwitz. That was when I saw my father for the last time. He was 56 years old.

They separated my mother and me. And all the family members—this was a very large family—everybody was annihilated. I spent three weeks in Auschwitz. Mengele dealt with us with a wave of his hand: this one this way, that one that way.

And when we arrived at Auschwitz, there were these Polish boys. You know, all of us arrived with kit-bags, with the things we were allowed to take, and they asked for them, saying, “You won’t see each other anymore, anyway, so you can give them away.” They said that in Yiddish. And we understood. We gave them all we had.

After three weeks of terrible Auschwitz torture we were selected by Mengele. I was a very thin girl already, I was in really bad condition, and I only saw—well, with my young mind anyway— that it was interesting that those who had been sent to the other side were in much better condition than myself. Well, I could see that.

I was just thinking this when a very big air raid came, the first serious one against Cracow, near Auschwitz.

There were Germans flat on their stomachs, and panic, and terrible screams. Meanwhile—I still don’t know why—I was down on my belly and I crawled over to those who looked better than me. They left us out on the ground for a night and later they took us into the fumigating chamber and the next day we got to Hessich-Lichtenau after a train-journey.

And those who were in the other group, to which I should have belonged, those were gassed that night. I still have those screams in my ears that we heard on the ground.

Read the english interview with Gáborné Révész here